When did the asteroids become minor planets?

by James L. Hilton

Discovery of the Asteroids

The controversy over whether Pluto should be given a minor planet number

and possibly be demoted from the ranks of the major planets reminds me of a

similar controversy that occurred 150 years ago. This controversy involved

whether or not the bodies discovered between Mars and Jupiter should be

considered equal to the seven other planets known at that time.

Titius von Wittenburg (1766)

discovered that the relative distances of the six known planets from the

Sun almost fit a simple relation. But it had a problem. It predicted there

should be a planet between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. In 1772 he

published a tract proposing that a planet should exist in the gap.

According to Cunningham

(1988), Johann Bode, director of the Berlin Observatory so popularized

this tract that the relation is now known as Bode's law.

In 1781 Uranus was discovered at just the distance where Bode's Law

predicted a seventh planet (including the gap between Mars and Jupiter)

should occur. This touched off a search for a planet in the gap between

Mars and Jupiter. The search ended, literally before it had begun, on

January 1, 1801 when Guiseppe Piazzi at the Palermo Observatory discovered

a 'star' that had moved from its position the previous night in the

constellation of Taurus (von

Zach 1801). Like Uranus, it was found to be a body at exactly the

distance predicted by Bode's Law. Two consecutive successes for a relation

that has no known physics behind it.

Piazzi named the new planet Ceres Ferdinandea after Ceres, the Roman

goddess of the harvest, and King Ferdinand IV of Naples and Sicily. The

second half of the name was dropped after several years for political

reasons. Thus, the gap was filled and the search ended.

Unexpectedly, on March 28, 1802 Heinrich Olbers discovered another small

body while observing Ceres. Its semi-major axis was nearly the same as

Ceres, and posed problems for the picture of the solar system that had been

emerging over the previous decades. Eventually, this new body was named

Pallas.

Neither of these bodies fit the conventional idea of a planet because

they were so small that their disks were nearly unobservable. Using a

projection system Herschel

(1802) determined 161.6 miles (260.0 km) for the diameter of Ceres and

147 miles (237 km) for Pallas. These results are nearly a factor of four

too small for Ceres and more than a factor of two too small for Pallas.

Because of this starlike appearance, Herschel declared, "From this, their

asteroidal appearance, if I may use that expression, therefore, I shall

take my name, and call them Asteroids; reserving for myself, however, the

liberty of changing that name, if another, more expressive of their nature

should occur." Thus Herschel argued that Ceres and Pallas were not the same

as the other planets.

However, other astronomers of the time thought otherwise. These two new

additions to the solar system were listed along with the rest of the

planets in order of increasing distance from the Sun. They were also given

symbols by their discoverers to be used when recording observations.

The symbols for the planets, shown in Table 1, were and are used as a

shorthand notation by astronomers, and others. To fulfill this role, they

are quick to draw, are easily distinguishable, and do not require much

skill to produce. Many of the symbols have several variants. The ones shown

in Table 1 are those almost universally adopted by the astronomical

community.

Table 1. The Symbols of the Sun, Moon, and Planets.

| Body | Symbol |

| Sun |  |

| Mercury |  |

| Venus |  |

| Earth |  |

| Mars |  |

| Jupiter |  |

| Saturn |  |

| Uranus |  |

| Neptune |  |

| Pluto |  |

| Moon |  |

The discoveries of Juno in 1804 and Vesta in 1807 raised concern in astronomers of

the day that the asteroids were fragments of a planet that had somehow disintegrated.

This theory was first proposed by Olbers upon the discovery of Pallas. However, Juno

and Vesta were added to the catalog of planets along with Ceres, Pallas, and, in

1846, Neptune.

The acceptance of the first four asteroids was so matter-of-fact that introductory

texts such as First Steps to

Astronomy and Geography (1828) lists the planets as, "Eleven: Mercury, Venus, the

Earth, Mars, Vesta, Juno, Ceres, Pallas, Jupiter, Saturn, and Herschel." Herschel was

an alternate name for Uranus (after its discoverer) used in Britain until the 1850's.

The Scene Becomes Complicated

The fifth asteroid, Astraea was discovered near the end of 1845, nearly 39 years

after the discovery of Vesta. The year 1847 saw the discovery of three new asteroids.

By the end of 1851 there were 15 asteroids, still listed by distance from the Sun.

Fourteen of them each had their own symbol; although, the symbol for Irene had never

been drawn, only described (Gould 1852)!

Some of these symbols, in Table 2, were quite fanciful and took significant artistic

skill to draw. Only the symbols for Ceres, Pallas, and Juno kept the same basic

simplicity of the symbols for the larger bodies in the solar system.

Table 2. The Old Symbols of the Asteroids. From

Gould (1852).

| Asteroid | Old Symbol |

| Ceres |  |

| Pallas |  |

| Juno |  |

| Vesta |  |

| Astraea |  |

| Hebe |  |

| Iris |  |

| Flora |  |

| Metis |  |

| Hygiea |  |

| Parthenope |  |

| Victoria |  |

| Egeria | Never assigned |

| Irene | "A dove carrying an olive-branch, with a star

on its head" (Hind 1852) (never

drawn) |

| Eunomia |  |

Encke (1851) made a major change in the

Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch, BAJ, for 1854. He said, "Finally, I want

to add that - in view of the complications and difficulties with the recently used

planetary symbols - I took the liberty to introduce the encircled numbers in stead of

symbols," (Translation by Schmaedel,

1999). However, there were some very definite differences from today's scheme. The

asteroids Encke was referring to began with Astrea which was given the number (1) and

went through (11) Eunomia. Ceres, Pallas, Juno, and Vesta continued to be denoted by

their traditional symbols. Not only that, but Ceres through Vesta continued to be listed,

in semi-major axis order along with the ephemerides of the major planets while Astrea

through Eunomia, and Neptune were relegated to a section at the end of the BAJ.

This innovation was immediately seized upon by the astronomical community at large.

American astronomer, B.A. Gould (1852)

noted:

As the number of known asteroids increases, the disadvantages of a symbolic notation

analogous to that hitherto in use increase much more rapidly even than the difficulty of

selecting appropriate names from the classic mythology. Not only are many of the symbols

proposed inefficient in suggesting the name of which they are intended to be an

abbreviation; but some of them require for their delineation more artistic accomplishment

than an astronomer is necessarily or generally endowed with.

To simplify this system he proposed a new set of symbols:

To remedy this evil, and not to lose the unquestionable advantage connected with a system

of symbols easily remembered and readily drawn,-it has been agreed upon by several

astronomers in Germany, France, England, and America, to propose for adoption a more

simple system for the group in question,-consisting of a circle containing the number of

the asteroid in the chronological order of its discovery.

The new system of symbols was designed to relieve the growing confusion and restore the

original intent of the symbols, a quick shorthand way of referring to solar system bodies;

not to give the asteroids a different status from the rest of the planets. However, Gould

did state, "...we thus have a symbol ready for every asteroid hereafter to be discovered,

and this remarkable group are distinguished from the larger planets in the character of

their notation."

In the BAJ for 1855 (Encke, 1852) the numbering of the minor planets at the back

began with (5) Astrea and goes through (15) Eunomia. Ceres through Vesta continued to be

listed in semi-major axis order with the major planets, using their old symbols. This

continued until the BAJ for 1867 (Encke, 1864) where they are listed as (1) Ceres,

(2) Pallas, (3) Juno, and (4) Vesta in order of discovery along with the other asteroids.

The first new asteroid for which the new symbol convention was used was (16) Psyche by

Ferguson (1852) in the publication of a

series of observations at the U.S. Naval Observatory.

However, at least three additional asteroids, (28) Bellona

(Encke, 1854), (35) Leukothea

(Rumker & Peters 1855), and (37)

Fides (Luther 1855), were given the

symbols in Table 3. The symbol for Leukothea, the most complicated of all, is described

by Rumker & Peters as representing an ancient lighthouse. However, there is no

evidence that these symbols were ever used outside of their initial publication in the

Astronomische Nachrichten.

Table 3. Symbols for the Asteroids Introduced after 1852.

| Asteroid | Symbol |

| (28) Bellona |  |

| (35) Leukothea |  |

| (37) Fides |  |

Cunningham (1988) states that this

set of symbols for the asteroids lasted until 1931 when it was replaced by a number

followed directly by the name; however, I have not been able to find an official notice

of the adoption of the present scheme of numbering asteroids. On the other hand, the

literature shows that several different schemes were used during the latter half of the

nineteenth century. The present form of number name is first found in the

Astronomische Nachrichten (1911).

The Change Occurs

The acceptance of the new system of symbols was extremely fast. The Astronomical

Journal, edited by Gould, adopted the new symbols immediately. The journal

Astronomische Nachrichten had

articles sporadically including the new symbols beginning 1854, and adopted them for its

index beginning in 1861. The Royal Greenwich

Observatory began labeling observations of the asteroids with the new symbols

beginning in 1858 with the publication of observations from 1856. The

Paris Observatory used them in its

table of contents in 1858, with the publication of its first volume of observations. And

the U.S. Naval Observatory adopted the use of the new symbols in 1863 with the

publication of its observations from 1852.

The two major almanacs that printed asteroid ephemerides at this time had interesting

reactions to the introduction of the new symbols.

The British The Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris had been

publishing ephemerides for Ceres, Pallas, Juno, and Vesta in order of their semi-major

axes between the ephemerides of Mars and Jupiter. In the volume for 1856, published in

1853, it stopped printing asteroid ephemerides altogether.

The BAJ continued to publish the ephemerides of the first four asteroids

discovered in semi-major axis order using the old symbols up through the volume for

1866, published in 1864. The ephemerides of the other asteroids were given in numerical

order in a section a section at the end of the BAJ along with the ephemeris for

Neptune. Beginning in 1852 there was also a table of opposition dates included at the

end of the asteroid ephemerides at the end of the BAJ. This table included the

opposition dates for Ceres through Vesta, indicating sort of a 'dual citizenship' for the

first four asteroids. Ceres through Vesta were not included with the other asteroids

until the edition for 1867, published in 1864. This was the first volume since the

introduction of the new symbols not published under the direction of Encke.

The BAJ evidently went so far as to announce a policy to refer to the asteroids

(60) and higher by their numbers only. This led

Förster (1861) to comment, "As for

naming planets, Berlin defines them by numbers only from planet (60) onwards,"

(Translation by Schmaedel, 1999).

However, the edition for 1864, printed in 1861, and all subsequent of the BAJ

refer to all the known asteroids by both number and name.

However, the advent of the new symbols also brought with it other changes. Except for

the U.S. Naval Observatory, all of the other publications immediately began publishing

their observations in order of their numerical symbol rather than their distance from the

Sun. The Paris Observatory also moved the observations of the asteroids to a section

separate from the observations of the other planets, while the Royal Greenwich

Observatory left the observations, in numerical order, between the observations of Mars

and Jupiter.

The Asteroids are Called 'Minor Planets'

The British The Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris had been producing

the elements of the asteroids under the heading of 'Minor Planets, Elements of' since its

volume for 1845, published in 1841. This is the only instance of the use of the phrase

'minor planet' I have found previous to the introduction of the new symbols for the

asteroids. Strangely, this section was dropped from the almanac along with the

ephemerides of Ceres, Pallas, Juno, and Vesta in the volume for 1856, published in 1853.

The first use of 'Kleine Planeten' after the introduction of the new system of symbols

was as 'kleine Planeten' in a paper by Jahn

(1854) in Astronomische Nachrichten. By 1861, the Astronomische Nachrichten

uses 'kleine Planete' as a subcategory to Planete (planet) in the index to collect the

articles on the asteroids. The Astronomische Nachrichten kept the asteroids as a

subcategory of the planets until it published its general index of volumes 181-210 in

1932 (Astronomische Nachrichten

1932).

Prior to 1866 the Paris Observatory

used the numerical symbols only in the table of contents. That year, the Paris

Observatory first uses the description 'petites planetes' in the observations. The

asteroids Ceres through Vesta, however, are conspicuously not included in the

category of 'petites planetes'. The observation of the first four asteroids are tabulated,

in order of discovery, not with the other planets, but in a section immediately before the

section titled 'Petites planetes'. Only beginning in 1868

(Paris Observatory 1868) are these four

bodies included with the rest of the 'petites planetes'. Like the BAJ the Paris

Observatory evidently gave Ceres through Vesta a sort of 'dual citizenship' until the

mid-1860's.

The U.S. Naval Observatory used the word 'asteroids' to describe the bodies between the

orbits of Mars and Jupiter until 1868. At that time it switched to using the term 'small

planets' (U.S. Naval Observatory 1868).

In 1892 it switched back to 'asteroid' (U.S.

Naval Observatory 1892) then to 'minor planet' in 1900

(Harkness & Skinner 1900), and

finally back to 'asteroid' in 1929 (Peters

1929).

The U.S. Nautical Almanac Office, an institution independent of the U.S. Naval

Observatory in the nineteenth century, generally mirrored the usage of the U.S. Naval

Observatory. Aside from a single usage of the term 'minor planet' in 1866, the

communications of the U.S. Nautical Almanac Office always referred to the asteroids as

either 'asteroids' or 'planets.' It is also clear that the Office desired to produce a

full set of ephemerides during a time in which it was struggling to establish itself and

produce its first volumes (Report of the

Nautical Almanac Office 1849-1896).

B.A. Gould at The Astronomical Journal never used the term 'minor planet,'

always opting for 'asteroid'. However, the asteroids were listed separately from the other

planets. Only with the publication of the index to volume 90 in 1985 of the Astronomical

Journal ( Astronomical Journal

1985), long after Gould's death, was the term 'minor planets' used. In December 1998,

the index of volume 116 of the Astronomical Journal uses the puzzling category of

'Minor Planets, Asteroids' ( Astronomical

Journal 1998).

The Royal Greenwich Observatory appears to have held out until after the turn of the

century. It continued to publish the observations of the asteroids between the observations

of Mars and Jupiter. However, they are listed in numerical order rather than in order of

semi-major axis. The title of the section was 'Observations of the Sun, the Moon, and the

Planets'. The Royal Greenwich Observatory never used either the word 'minor' or 'asteroid'

in regard to any of its observations of solar system bodies until the publication of its

1905 observations (Royal Greenwich Observatory

1907).

Thus, the term 'minor planet' was quickly adopted by the astronomical community. But,

its acceptance was not universal.

The Sizes of the first three asteroids shrink

At the time the description 'minor planet' began to be used, the most widely

disseminated values for the diameters of the first four asteroids discovered were Ceres,

2613 km; Pallas, 3380 km; Juno, 2290 km; and Vesta, "not more than 383 km"

(Hughes 1994). The diameters of the first

three asteroids were derived from direct estimates of the sizes of their disks by

Schroter (1811) and are directly comparable

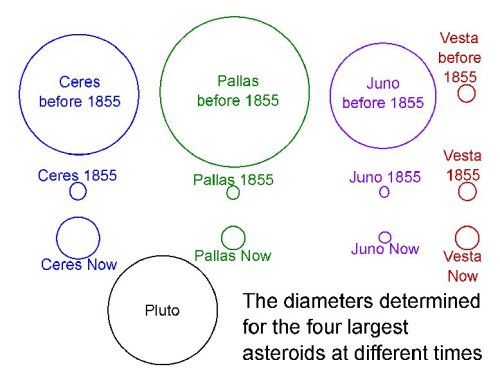

to the 2390 km of Pluto. The pre-1855 asteroid diameters, shown in Figure 1, are grossly too

large.

Fig.1. The diameters determined for the four largest asteroids at different

times. The diameter of Pluto is included for purposes of comparison.

Conversely, the first determination of the diameters of the asteroids after the use of

the term minor planets began to be used were too small.

Stampfer (1856) produced diameters of 350,

270, 200, and 400 km for Ceres, Pallas, Juno, and Vesta respectively. These diameters were

based on photometry rather than trying to measure the angular diameter directly. However,

the albedos chosen were more like that of an icy body in the outer solar system rather than a

rocky body of the inner solar system which these asteroids more closely resemble.

Just as the earlier diameters determinations made as 'planets' were way too large, the

first 'minor planet' diameters were way too small. In both cases the size determined depended

on the assumptions that went into interpreting the data. The question that can not be

answered is, "How much were these assumptions colored by how the observers thought of the

bodies they were observing?" In either case, the assumptions made were not necessarily

warranted.

Nonsymbolic symbols

Finally, the use of the numbers as part of a symbolic shorthand for the asteroid names

appears to have lost its symbolism shortly after it was introduced.

Here again The Astronomical Journal

(1858) led the way. Beginning in 1858 it marked newly discovered asteroids by enclosing

their number in parentheses rather than a circle. Once the asteroid's orbit was firmly

established, the symbol was then changed to the number enclosed by a circle. This format

lasted only until 1888 when it switched to the number followed by the name separated by a

comma (Astronomical Journal 1888).

Finally, in 1895 it switched back to using parentheses for all asteroids and always followed

by the asteroid's name (Astronomical Journal

1895).

The U.S. Naval Observatory (1868) adopted

the parentheses followed by the name for the asteroids in 1868. In 1872 it replaced the

parentheses with a circle, but kept the name

(U.S. Naval Observatory 1895). It used this

convention until 1949. At this time only the first four asteroids, Ceres, Pallas, Juno, and

Vesta, which it referred to by name only, were observed

(Watts & Adams 1949).

The Astronomische Nachrichten (1872)

started using parentheses followed by the name for all asteroid numbers in 1872. And then

switched to the present day format of number and name without circle, parentheses, or comma

in 1911 (Astronomische Nachrichten 1911).

The Paris Observatory kept the number within a circle symbol right up to 1908, but always

gave the name along with the symbol.

Cunningham (1988) asserts that the

symbol of a number enclosed by a circle was the official designation for asteroids until 1931

when the current nomenclature of the number, sometimes enclosed in parentheses in paper titles

and indices, followed by the name without a separating comma was adopted. However, I do not

know of any agreement codifying this. It is also clear that the number name designation had

become the de facto standard in the literature by evolution over the 73 years between 1858 and

1931. The number in a circle for an asteroid had quickly lost its nature as a symbol and

merely become an accounting tool for the ordering of the asteroids.

Conclusions

Along with the adoption of a new set of symbols that easily separated the asteroids from

the other planets, it appears that the change from planet to minor planet happened very

quickly. It was recognized from the beginning that these bodies did not fit along with the

rest of the planets, but during the years in which the number of known asteroids was small,

they were included on the list of solar system bodies just as if they were regular planets.

However, once their numbers grew too large to fit the existing scheme of classification, their

uniqueness was quickly recognized and a new class of solar system objects was created.

The event that appears to have triggered this reevaluation of the asteroids was the

introduction of a new set of symbols to use as a shorthand notation for them. The new set of

symbols had nothing to do with judging whether or not the asteroids were planets. They were

designed to restore the reason for having the symbols in the first place, a quick convenient

method of referring to a body. Nor is it clear that the name 'minor planet' was meant to

separate the asteroids from the other planets. However, the introduction of the new system of

symbols had the unintended consequence of reordering the asteroids from the traditional

ordering of the planets, by semi-major axis, to numerical order and setting them apart from

the other planets. This separation allowed a new category of solar system objects to be

recognized.

The BAJ and the Paris Observatory accorded Ceres through Vesta a form of 'dual

citizenship' with both the planets and the asteroids through the mid-1860's. The failure of

this dual categorization is noteworthy because Ceres, the first asteroid discovered, is

estimated to contain 30-40% of the mass of the asteroid belt, while Pallas and Vesta combined

are nearly as massive as Ceres. Because they fit the mold of a minor planet better than that

of a regular planet, even these largest asteroids are considered minor planets after more

than 50 years of being accepted as planets like Jupiter, Saturn, and Mercury.

The label of 'minor planet' also appears to have had almost immediate consequences in

terms of assumptions made in determining their diameters. Almost immediately after the term

'minor planet' was adopted a new determination of the diameters of the first three asteroid

produced values only 10% of those previously adopted, and much smaller than today's accepted

values. Although the methods used in the different eras changed radically, they both required

that the observer make assumptions in reducing the data. These assumptions may have been

colored by how the observers thought of the asteroids.

Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge the works of

C.J. Cunningham (1988) and

D.W. Hughes (1994). They were both invaluable

in finding starting points for the primary sources on the history of the discovery of the

asteroids and their diameters, respectively. I also would like to acknowledge R.A. Kowalski

(1999, private communication) whose talk "A Brief History of Minor Planet Research," describes

a somewhat different picture than the one I first formed on this subject.

References

Astron. J. 1858, 5, 193-201.

Astron. J. 1888, 7, 193.

Astron. J. 1895, 12, 207-213.

Astron. J. 1985, 90, 2672.

Astron. J. 1998, 116, 3113.

Astronomische Nachrichten 1854, Register zu Band, 38, 394.

Astronomische Nachrichten 1861, Register zu Band, 54, 394.

Astronomische Nachrichten 1872, Register zu Band, 79, 398-401.

Astronomische Nachrichten 1911, Register zu Band, 180, 467.

Astronomische Nachrichten 1932, General Index to Volumes 181-210, 213-338.

Cunningham, C.J. 1988, Introduction to Asteroids, (Willmann-Bell: Richmond, VA).

Encke, J.F. 1851, Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch for 1854, (Berlin).

Encke, J.F. 1854, Astronomische Nachrichten, 38, 143.

Ferguson, J. 1852, Astronomische Nachrichten, 35, 51.

First Steps to Astronomy and Geography 1828, (Hatchard & Son: Piccadilly, London).

Förster, W. 1861, Astronomische Nachrichten, 55, 116.

Gould, B.A. 1852, On the Symbolic Notation of the Asteroids, Astron. J., 2, 80.

Herschel, W. 1802, Phil. Trans. Royal Society.

Harkness, W. & Skinner, A.N. 1900, "Transit circle Observations of the Sun, Moon, Planets,

and Miscellaneous Stars 1894–1899," Publications of the U.S. Naval Observatory 2nd Series, vol. 1, 397.

Hind, J.R. 1852, From a Letter of Mr. Hind to the Editor, Astron. J., 2, 22-23.

Hughes, D.W. 1994, The Historical Unraveling of the Diameters of the First Four Asteroids,

Q. J. R. Astr. Soc., 35, 331-344.

Jahn, G.A. 1854, "Ueber die gegenseitige Lage der Bahnen der kleine Planeten," Astronomische

Nachrichten, 38, 81-84.

Luther, R. 1855, Astronomische Nachrichten, 42, 107.

Paris Observatory 1858, Annales de l'Observatoire Impérial de Paris

Publiées, 1, 381–387.

Paris Observatory 1866, Annales de l'Observatoire Impérial de Paris

Publiées, 10, 239–244.

Paris Observatory 1868, Annales de l'Observatoire Impérial de Paris

Publiées, 19, I44–I52.

Peters, G.H. 1929, "Asteroid Observations by Photographic Methods," Publications of the U.S.

Naval Observatory 2nd Series, vol. 12, Part 2, 347-526.

Various authors (1849–1896), "Report of the Nautical Almanac Office" in Report of the

Secretary of the Navy.

Royal Greenwich Observatory 1858, Observations for the Year 1856, 27-34.

Royal Greenwich Observatory 1907, Observations for the Year 1905

Rumker, G. & Peters, C.A.F. 1855, Astronomische Nachrichten, 40, 373.

Schmaedel, L. 1999, Dictionary of Minor Planet Names, 4th ed., (Springer: Berlin).

Schroter, J.H. 1811, Lilienthalsche Beobachtungen der

neuerentdeckten Planeten Ceres, Pallas, und Juno, zur genauen und richitigen Kenntniss iher 1805 wahren Grossen,

Atmospharen, und ubrigen merkwurdigen Naturverhaltnisse im Sonnengebiete, etc.

Stampfer, see Bruhns, C.C. 1856, De Planetis Minoribus inter Martem et Jovem circa Solem

versantibus, Berlin.

Titius von Wittenburg 1766, Betrachtung uber die Natur, vom Herrn Karl Bonnet, p. 7,

Leipzig (translation into German from French).

U.S. Naval Observatory 1868, Washington Observations for 1866, 401.

U.S. Naval Observatory 1892, Washington Observations for 1888, C20.

U.S. Naval Observatory 1895, Washington Observations for 1890, pp. 88, 97-99.

von Zach, F. 1801, Monthly Correspondence, 3, 602.

Watts, C.B. & Adams, A.N. 1949, "Results of Observations made with the Six-Inch Transit

circle 1925–1941," Publications of the U.S. Naval Observatory 2nd Series, vol. 16, Part 1, 200-203 .